Historically, "grey" approaches to implementing urban infrastructure (so called due to the color of pavement and pipes) have been the norm in the United States. However, with increased public awareness of environmental issues, and pressure on public officials to embrace green building and management strategies and constrain the skyrocketing costs of grey projects, a movement is underway to use "green" infrastructure to counteract the environmentally damaging impact of urbanization. A particularly acute problem that merits intervention with green strategies - and one where knowledge modeling and geospatial technologies show promise - is that of urban stormwater and its associated pollution.

Rain that falls on the impermeable surfaces of an urban landscape collects a variety of chemicals, toxins and dangerous organisms. If not properly managed, this contaminated rainwater makes its way into, and pollutes, the rivers, lakes and other bodies of water upon which we depend for drinking water, fishing and recreation. Precipitation that becomes urban stormwater may go largely unnoticed by the general population. However, urban stormwater is a major, cumulative and growing source of pollutants that threatens our health, wildlife and environment.

Stormwater and the infrastructure to manage it are generally taken for granted in the U.S., but urban growth is taxing existing and aging physical systems in many locations. With ever more built or paved surfaces replacing natural vegetation, stormwater volume and the infrastructure needed to manage it are increasing problems in many metropolitan areas, especially in the face of significant wet weather events.

For example, in Portland, Oregon, a city well-known for its rainfall, sewers that carry both runoff and sewage often fill beyond capacity. During these combined sewer overflows (CSOs), sewers are designed to route and discharge untreated sewage and stormwater directly into nearby bodies of water rather than allowing it to back up into streets and basements. In Portland, CSOs carry harmful material and bacteria from both stormwater and wastewater directly into the Willamette River, which runs through the heart of the city.

The city of Portland is addressing this problem, in part, through a $1.4 billion "grey" public works project that will reduce CSOs by an estimated 65 percent when it is complete in 2011. This undertaking includes the construction of various big pipes, including a 22-foot diameter, 6-mile long, 83 million gallon-capacity tunnel on the east side of the city.

As Portland’s efforts make clear, keeping pace with infrastructure improvements needed to manage stormwater can be a significant economic hardship for city management. Yet despite the enormous cost, the city risks outgrowing its extensive pipe and pumping project in the future. Moreover, the approach is expensive, invasive and inconvenient. While effective in the short term, implementing a large infrastructure project is not a complete solution. Addressing stormwater and other energy and sustainability challenges through the implementation of traditional grey infrastructure often does not scale adequately, is not possible given limited financial resources and ignores the multiple benefits of "greener" solutions.

Taking an alternative approach, the city has inspired individual property owners to act on Portland’s stormwater challenge by disconnecting their downspouts. By giving citizens discounts off their water bill to alter their stormwater footprint, the city has diverted about one billion gallons annually from the combined sewer system - an investment of approximately $8 million that will save the city $250 million in infrastructure improvements.

This program signals a broader paradigm shift, acknowledging that it is much less expensive to act on precipitation at its source (as it comes from the sky) than after it reaches the pavement, collects pollutants and begins to travel. And individual action, such as disconnecting a downspout on private property, can contribute to a larger solution. In other words, viewing the problem of stormwater management as one of resource modeling, goal optimization and community action can help mitigate the need for costly infrastructure aimed solely at managing stormwater treatment and disposal.

In addition to disconnecting downspouts, citizens can make a difference by removing from their private property invasive plant species that contribute to poor water filtering and soil erosion, and planting native trees and shrubbery that increase absorption of rainwater and improve water filtering efficiency. However, cities need information technology and tools to foment, direct and measure these community actions, and municipalities must appeal to their constituents in ways that address specific personal concerns and provide meaningful economic incentives for voluntary actions.

Semantic knowledge modeling software provider Thetus Corporation aims to provide citizens and city leaders in Portland with an online toolset to effect change in the way individuals, neighborhoods and cities understand and manage the environmental impact of stormwater on a household-by-household basis. Thetus set out to tailor its semantic knowledge modeling technology to an interactive online platform with comprehensive lot data and geospatial mapping tools. Tupolo is a goal and projection modeling solution geared toward sustainability. It is built on the Thetus Publisher semantic knowledge modeling platform and has decision maker and constituent components that can be used in concert. Tupolo Storm is an application for managing stormwater systems that offers consumers a hands-on, GIS-supported user experience. It enables property owners to visualize and manipulate their homes’ stormwater dynamics and to take advantage of incentives from business and city organizations to improve their stormwater footprint. For city leaders, the platform acts as a management tool through which program variables can be controlled, results reported and outcomes analyzed. (In fact, the platform exports summary reports in PowerPoint format for ease of sharing, as well as Google Earth .kml files with robust reporting information.)

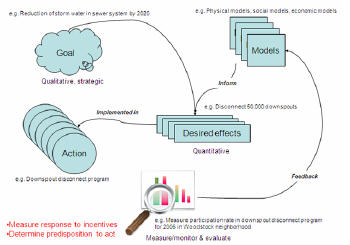

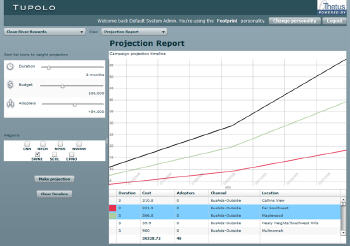

The approach used for the Tupolo Storm application centers on existing data, evolving conceptual models and customized system models. As actions are taken, the system tracks the use of best management practices and marketing campaign activity, reports results and projects impacts for consumption by decision makers (figure 1). It also has an extensive set of tools for campaign planning and goal visualization. The system uses GIS data, marketing campaign data, a model for best management practices, physical, social and economic conceptual models, and automated tasks. It leverages the power of a semantic knowledge base to capture, track and relate evolving data and metadata, to improve and refine the models, to connect goals with incentives and campaign performance information, and to provide meaningful visualizations and reporting.

|

Consumer Actions

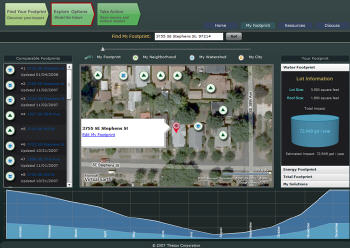

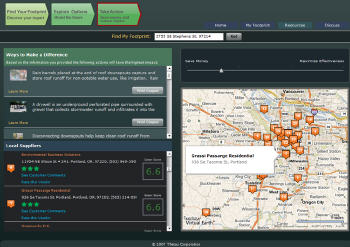

From a consumer perspective, the user is presented with a dashboard that, through the integration of geospatial data, offers the ability to access a specific address (figure 2). The application leverages data such as lot line, house layout, soil type, existing slope, watershed and sewer basin data, and presents the user with a visual representation that acts as a basis for water exploration. The user can manipulate this representation and dynamically view the impact that changes would make in water runoff. Basic actions include disconnecting downspouts and adding trees, planters, grass and shrubbery to property. More involved actions might include installing a green roof, planting a rain garden, implementing a water barrel and cistern system, and installing permeable pavements in place of impervious surfaces such as concrete driveways.

|

In configuring their lots, residents can compare their water impact with their neighbors and with improvements aimed at mitigating stormwater, find vendors who offer selected products and services. Couponing and other incentives, such as special offers from nurseries and home stores or for gutter maintenance, which serve to "close the loop," are used to track consumer actions.

On the back end, as users make lot configuration changes, the system uses known coefficients relating to the pervious/imperviousness of individual surfaces to make calculations regarding runoff impact that is dynamically reflected in the editor lot view.

|

|

Policymakers

Policymakers may fall into several groups in stormwater management; financial modelers, sustainability professionals, community outreach leaders, engineering staff and political officials. Each of these groups has different sets of information they need to be able to see and understand in order to do their respective jobs.

All of these policymakers need to see a current view of the situation in order to be able to assess where marketing campaigns are working and what their impacts will be.

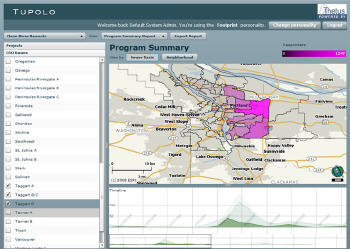

In figure 5, policymakers can understand activities by neighborhood and watershed. They can compare different regions and easily identify regions of concern.

|

Figure 6 shows one of the goal modeling tools that allows policymakers to set marketing campaign parameters (budget, target adoptees, time and region), to prioritize these parameters and to be provided with sets of candidate programs that will help them achieve desired outcomes. The system then monitors actual progress against projections.

|

The Tupolo Storm solution brings previously untapped private market forces to bear on a complex environmental problem. It promotes public education and outreach regarding the problem and provides intelligence about public behavior in response to marketing campaigns to inform future planning and programs targeting the problem.

The Tupolo solution is extensible to locations other than the example Portland provides and to problem spaces other than stormwater. The knowledge base at the core of the solution is not dependent on geospatial location or specific lot data. Rather, it is based on a semantic framework and conceptual models comprised of definitions and relationships that can be abstracted and applied to data from any urban area and to applications relating to energy, carbon and waste/recycling management. As Portland’s example shows, where cities are confronted with difficult infrastructure improvements and escalating expense, knowledge models and geospatial technologies can offer real-world solutions that link municipal objectives to community action, presenting a path to powerful results and significant cost savings.