Directions Magazine (DM): We think of Avencia as a services company, rather than as a products company. What prompted the company to develop and offer products such as Sajara?

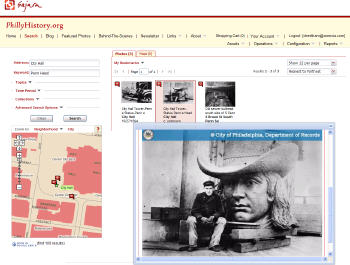

Avencia: Avencia continues to derive most of its revenue from professional services work. When we would present projects like PhillyHistory.org at conferences, we would hear comments like, "If you ever turn this into a more generic product, give me a call." Over the past three years, we have embarked on an effort to distill the best parts of a few of our projects into a set of Web-based "solution frameworks" that can be rapidly implemented in a variety of contexts. Most of these began as professional services projects or as inquiries regarding professional services work, but have grown into more generic solutions. We now have five such projects under active development:

- Sajara

- DecisionTree (a geographic prioritization system)

- Kaleidocade (Indicators Framework supports analysis and visualization of geographically aggregated data)

- Cicero (a Web API that enables developers to geocode an address and find the associated legislative district or school district)

- HunchLab (enables identification of statistically significant changes in geographic events such as crime)

DM: How is Sajara different from other document management solutions used for digital assets in general and geospatial ones in particular?

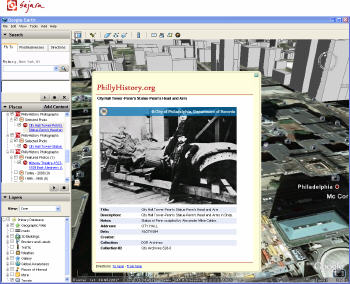

Avencia: Sajara combines the power of geography with the search and metadata management features of a conventional digital asset management system. It can be configured to work with a number of different geocoding solutions in order to geographically tag each photo, document, video or audio clip stored in the asset database. Visitors to a Sajara-powered site can search assets by address, intersection, place name or neighborhood, as well as the more conventional keywords, categories, collections and dates. In the most recent version, we have added support for geographic assets that cover areas, such as scanned map images. This is fairly unique. While a few asset management systems have geographic search capabilities, they are usually limited to searching point locations.

In addition to geographic search, we have been working hard to add new features that support integration with other systems. Sajara has a simple API that supports linking to specific search parameters from external sites. Any search in Sajara can also now be turned into a GeoRSS feed, enabling visitors to keep track of new photos in their neighborhood, for example, but also enabling display in other systems, such as GoogleMaps. We also recently added display of assets and search results as KML in GoogleEarth. Last summer, we rolled out a mobile version that provides a stripped-down search system for any mobile device with Web access. So you can now be standing on a street corner, type in an address or intersection, and both find and display the assets around you. Finally, Sajara has a configurable product catalog, shopping cart and order fulfillment features and can be integrated with credit card systems. Many of the government and non-profit clients with which we work are looking to not only improve public access to documents, but also generate new sources of revenue. These features enable them to support sales of photo prints or other products. We think Sajara is a pretty unique product, but we are constantly looking for new ways to improve it.

|

|

Avencia: We don’t actually think most of our clients are really interested in OpenLayers or Ext JS, per se. We built the original version of Sajara by developing a custom map control for the ESRI ArcIMS product. We moved to the open source OpenLayers toolkit because it would enable us to support a broad range of mapping engines including ArcIMS, ArcGIS Server, GeoServer, MapServer, GoogleMaps and others. So flexibility for our clients is part of the story. But it’s also about the development cost. OpenLayers has a strong developer community that releases new capabilities far more quickly than we could support on our own. By leveraging the work of this larger community, we can implement new features more quickly.

|

The reasoning behind Ext JS is a little different. Over the past couple of years, the increased use of AJAX to create a more interactive Web interface has led to a far more complex software development environment on the Web. Our engineers were increasingly spending their time dealing with "browser hacks" – workarounds to deal with the fact that the various browsers and versions implement Javascript, CSS, XML and HTML in different ways. There are a couple of different approaches to solving this problem. One option is to avoid the issues by getting rid of the HTML/CSS/Javascript legacy completely. The Adobe Flex and Microsoft Silverlight platforms are one way to do this. The other option is to embrace HTML/CSS/Javascript more fully, but to abstract the browser-specific features. Ext is just one of several development toolkits that do this. Others include: Dojo, Prototype, jQuery, YUI and Scriptaculous. As a company, we are taking both approaches. For some of our projects, we are using Flex – DecisionTree is one of these. For others we are using Ext JS in combination with a map display toolkit. OpenLayers is a great one, but we are also using Ext with the ESRI Web ADF.

DM: How big is the Sajara user community?

Avencia: As a software solution, Sajara is primarily being targeted at the archive, museum, library and tourism markets, but we have also had interest from unexpected places. For example, we are working on a new Sajara implementation with the Mural Arts Program to make a comprehensive database of its urban mural projects.

DM: Has the recent growth of interest in geospatial on the Web changed demands on digital asset management? How?

Avencia: The big change in digital asset management is the Web itself. Organizations such as historical societies, archives, museums and libraries are increasingly being urged by their boards and the general public to make the content of their collections available to the public. This is not an easy transition as much of the metadata is still maintained in desktop asset management systems. Moving to the Web introduces a host of questions such as digital rights management, licensing and the potential for increased costs to support and maintain these new systems.

That said, many of these organizations are making that transition to the Web and geospatial is a part of it. In most cases, the physical collections are not indexed or stored based on geography at all. Collections are often organized by the person or organization that contributed them and then sometimes based on time (through an accession number or similar mechanism). Where digital metadata exists, additional data such as topic, keyword, title and creator name are frequently attached. But rarely is there a field dedicated to storing location information, let alone a geographic coordinate pair. And yet, for many collections, the public primarily wants to find photos, drawings, and paintings based on location. There are homeowners who want an historic photo of their block or favorite place. There are real estate agents, developers or retail stores who want to add some local historical texture to their interiors. There are genealogists, neighborhood historians and design professionals performing environmental due diligence. So location is very important. When an organization wants to begin supporting location-based searching, the first step is usually to extract location text from a description, title or logbook. Avencia has sometimes used vocabularies of street and place names to help extract place name information from unstructured text, and companies like MetaCarta have turned this process into a highly successful business.

Once we have some location text, the tools and databases for assigning coordinates exist from many sources. However, historical materials introduce a special challenge. While our databases of contemporary streets and place names are becoming robust and continue to improve with each passing year, we are not yet working on an historical street grid. For communities that have been established and grown up in the post-World War II era, this is not a huge problem, but for older places that have supported human settlement for centuries, this is an enormous issue. To take the Philadelphia example, while what we know today as "Center City" was laid out by William Penn on a grid and many of his original street names survive, the addressing system in 18th and early 19th century Philadelphia was different from what it is today. To begin with, address numbers were assigned based on the temporal sequence in which a structure was built, rather than the linear spatial sequence that we take for granted in most of the United States and Canada today. This was all changed when Philadelphia underwent "The Consolidation" in the 1854. At that time, dozens of outlying townships and boroughs were consolidated into a single city/county. Of course, every town had its own Market St and Chestnut St, so in order to avoid confusion, most of the city’s street names were changed to new ones and over the next 60 years, there were successive waves of street re-naming events to bring order to the addresses. And, of course, city councils all over the world have been busy memorializing historical figures by re-naming part or all of a street after a prominent person. Now imagine that process and its many variants played out over many centuries around the world in Tokyo, Cairo, Osaka, London, Saigon, Hong Kong, Paris and Rome.

We began running into this issue with the PhillyHistory.org implementation very early in the process of digitizing and tagging the photos with geographic coordinates. While capturing photographs of government activity did not really begin until after Consolidation, the problem remained substantial for records dating from the 1860s to the 1920s. We began to build an Historic Street Name Index whereby we could start to keep a record of street name changes we encountered. The effort got a shot in the arm from a local historian, Jefferson Moak, who had once worked in the City Archives and now works at the National Archives. Moak had basically been creating a spreadsheet of these street name changes over many years based on city council ordinances he encountered in his research. He graciously agreed to contribute his spreadsheet to the effort. Since then, we have reserved a few hours a week for our hard-working graduate student interns to extend and expand this database. An interim version of the database is available. We now have an internal R&D project focused on creating both Web-based tools and a database design to store a temporal street centerline - each street segment, gazetteer point or neighborhood boundary has one or more names attached to it and each name has a timespan associated with it. The long-term goal is to construct a temporal geocoder - a Web service that will accept not only an address or place name but also a time.

We are a small company, so there is a limit to how much R&D we can do without a client or grant to support it, but we are plugging away at it. We doubt there is much financial incentive for the base mapping companies like NAVTEQ and TeleAtlas to invest in this, so we suspect that it will require an open data project like OpenStreetMap or GeoNames in order to capture the knowledge of historians out there. But as our databases of contemporary geography are filled out, there is increasing interest in what we can learn from historical geography. We think it is significant that Anne Kelly Knowles, who co-edited the recently released book, Placing History, will be the keynote speaker at this summer’s ESRI User Conference.