Part III - Collection

The collection function rests on research - on matching validated intelligence objectives to available sources of information, with the results to be transformed into usable intelligence. Just as within needs-definition, analysis is an integral function of collection.

Collection Requirements

The collection requirement specifies exactly how the intelligence service will go about acquiring the intelligence information the customer needs. Any one, or any of several, players in the intelligence system may be involved in formulating collection requirements: the intelligence analyst, a dedicated staff officer, or a specialized collection unit.

In large intelligence services, collection requirements may be managed by a group of specialists acting as liaisons between customers and collectors (people who actually obtain the needed information, either directly or by use of technical means). Within that requirements staff, individual requirements officers may be dedicated to a particular set of customers, a type of collection resource, or a specific intelligence issue. This use of collection requirements officers is prevalent in the government. Smaller services, especially in the private sector, may assign collection requirements management to one person or team within a multidisciplinary intelligence unit that serves a particular customer or that is arrayed against a particular topic area.

Regardless of how it is organized, the requirements management function entails much more than simple administrative duties. It requires analytic skill to evaluate how well the customer has expressed the intelligence need; whether, how and when the intelligence unit is able to obtain the required information through its available collection sources; and in what form to deliver the collected information to the intelligence analyst.

Collection Planning and Operations

One method for selecting a collection strategy is to first prepare a list of expected target evidence. The collection requirements officer and the intelligence analyst for the tar-get may collaborate in identifying the most revealing evidence of target activity, which may include physical features of terrain or objects, human behavior, or natural and man-made phenomena. The issue that can be resolved through this analysis is "What am I looking for, and how will I know it if I see it"?

Successful analysis of expected target evidence in light of the customer's needs can determine what collection source and method will permit detection and capture of that evidence. Increasingly sophisticated identification of evidence types may reveal what collectible data are essential for drawing key conclusions, and therefore should be given priority; whether the evidence is distinguishable from innocuous information; and whether the intelligence service has the skills, time, money and authorization to collect the data needed to exploit a particular target. Furthermore, the collection must yield information in a format that is either usable in raw form by the intelligence analyst, or that can be converted practicably into usable form.

For example, in the case of the first business scenario presented in Part II, the CEO needs intelligence on why and how the similar, competitor company suddenly reorganized its production department. The collection requirement might specify that the intelligence unit give first priority to this new issue; it will focus on collecting information about the competitor's reorganization. A list of relevant evidence might include the following: changes in personnel assignments, changes in supply of production components, budget deficit or surplus, age of infrastructure, breakthroughs in research and development, and changes in the cultural or natural environment. To exploit this evidence, the intelligence service would thus need direct or indirect access to information on the company's employees, its previous production methods, its financial status, its physical plant, its overall functional structure and operations, and the consumer market. The collection unit would choose from among the sources listed in Table 7 below those most likely to provide timely access to this information in usable form.

Finally, upon defining the collection requirement and selecting a collection strategy, the intelligence unit should implement that strategy by tasking personnel and resources to exploit selected sources, perform the collection, re-format the results if necessary to make them usable in the next stages, and forward the information to the intelligence production unit. This aspect of the collection phase may be called collection operations management. As with requirements management, it is often done by specialists, particularly in the large intelligence service. In smaller operations, the same person or team may perform some or all of the collection-related functions.

The small, multidisciplinary intelligence unit may experience certain benefits and disadvantages in managing multiple phases of the intelligence process at the same time. In comparison to the large, compartmentalized service, the smaller unit will likely experience greater overall efficiency of operations and fewer bureaucratic barriers to customer service. The same few people may act as requirements officers, operations managers and intelligence analysts/producers, decreasing the likelihood of communication and scheduling problems among them. This approach may be less expensive in terms of infrastructure and logistics than a functionally divided operation. On the other hand, the financial and time investment in training each individual in every facet of the intelligence process may be substantial. Furthermore, careful selection and assignment of personnel who thrive in a multidisciplinary environment will be vital to the unit's success, to help ward off potential worker stress and overload. An additional pitfall that the small unit should strive to avoid is the tendency to be self-limiting: over-reliance on the same customer contacts, collection sources and methods, analytic approaches, and production formulas can lead to stagnation and irrelevance. The small intelligence unit should be careful to invest in new initiatives that keep pace with changing times and customer needs.

Collection Sources

The range of sources available to all intelligence analysts, including those outside of government, is of course much broader than the set of restricted, special sources available only for government use. U.S. government collection of information for intelligence purposes is channeled through the recognized intelligence collection disciplines described in Part I. From a different perspective, four general categories serve to identify the types of information sources available to the intelligence analyst: people, objects, emanations, and records. Strictly speaking, the information offered by these sources may not be called intelligence if the information has not yet been converted into a value-added product. In the government or private sector, collection may be performed by the reporting analyst or by a specialist in one or more of the collection disciplines. The following table, derived from Clauser and Weir, illustrates the distinct attributes offered by the four sources of intelligence.36

|

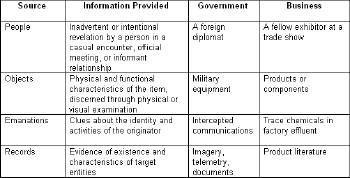

The following table offers examples from government and business of each source type.

|

The collection phase of the intelligence process thus involves several steps: translation of the intelligence need into a collection requirement, definition of a collection strategy, selection of collection sources, and information collection. The resultant collected information must often undergo a further conversion before it can yield intelligence in the analysis stage. Processing of collected information into intelligence information is addressed in the following Part of this primer.

Reference

36Jerome K. Clauser and Sandra M. Weir, Intelligence Research Methodology: An Introduction to Techniques and Procedures for Conducting Research in Defense Intelligence (Washington, DC: Defense Intelligence School, 1975), 111-117.