Part I - Intelligence Process

Intelligence is more than information. It is knowledge that has been specially prepared for a customer's unique circumstances. The word knowledge highlights the need for human involvement. Intelligence collection systems produce ... data, not intelligence; only the human mind can provide that special touch that makes sense of data for different customers' requirements. The special processing that partially defines intelligence is the continual collection, verification, and analysis of information that allows us to understand the problem or situation in actionable terms and then tailor a product in the context of the customer's circumstances. If any of these essential attributes is missing, then the product remains information rather than intelligence.18

The intelligence profession, already well established within government, is growing in the private sector. Intelligence is traditionally a function of government organizations serving the decision-making needs of national security authorities. But innovative private firms are increasingly adapting the national security intelligence model to the business world to aid their own strategic planning. Although business professionals may prefer the term "information" over "intelligence," the author will use the latter term to highlight the importance of adding value to information. According to government convention, the author will use the term "customer" to refer to the intended recipient of an intelligence product - either a fellow intelligence service member, or a policy official or decision maker. The process of converting raw information into actionable intelligence can serve government and business equally well in their respective domains.

The Intelligence Process in Government and Business

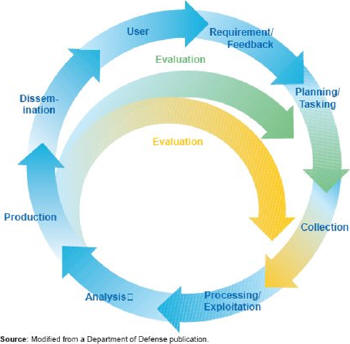

Production of intelligence follows a cyclical process, a series of repeated and interrelated steps that add value to original inputs and create a substantially transformed product. That transformation is what distinguishes intelligence from a simple cyclical activity.19 In government and private sector alike, analysis is the catalyst that converts information into intelligence for planners and decision makers.

Although the intelligence process is complex and dynamic, several component functions may be distinguished from the whole. In this primer, components are identified as Intelligence Needs, Collection Activities, Processing of Collected Information, Analysis and Production. To highlight the components, each is accorded a separate Part in this study. These labels, and the illustration below, should not be interpreted to mean that intelligence is a uni-dimensional and unidirectional process. "In fact, the [process] is a multidimensional, multi-directional, and - most importantly - interactive and iteractive."20

|

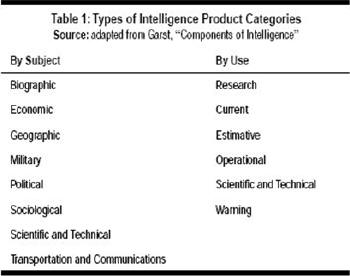

The purpose of this process is for the intelligence service to provide decision makers with tools, or "products" that assist them in identifying key decision factors. Such intelligence products may be described both in terms of their subject content and their intended use.

|

Any or all of these categories may be relevant to the private sector, depending upon the particular firm's product line and objectives in a given industry, market environment, and geographic area.

A nation's power or a firm's success results from a combination of factors, so intelligence producers and customers should examine potential adversaries and competitive situations from as many relevant viewpoints as possible. A competitor's economic resources, political alignments, the number, education and health of its people, and apparent objectives are all important in determining the ability of a country or a business to exert influence on others. The eight subject categories of intelligence are exhaustive, but they are not mutually exclusive. Although dividing intelligence into subject areas is useful for analyzing information and administering production, it should not become a rigid formula. Some intelligence services structure production into geographic subject areas when their responsibilities warrant a broader perspective than topical divisions would allow.22

Similarly, characterization of intelligence by intended use applies to both government and enterprise, and the categories again are exhaustive, but not mutually exclusive. The production of basic research intelligence yields structured summaries of topics such as geographic, demographic, and political studies, presented in handbooks, charts, maps, and the like. Current intelligence addresses day-to-day events to apprise decision makers of new developments and assess their significance. Estimative intelligence deals with what might be or what might happen; it may help policymaker's fill in gaps between available facts, or assess the range and likelihood of possible outcomes in a threat or "opportunity" scenario. Operational support intelligence incorporates all types of intelligence by use, but is produced in a tailored, focused, and timely manner for planners and operators of the supported activity. Scientific and Technical intelligence typically comes to life in in-depth, focused assessments stemming from detailed physical or functional examination of objects, events, or processes, such as equipment manufacturing techniques.23 Warning intelligence sounds an alarm, connoting urgency, and implies the potential need for policy action in response.

How government and business leaders define their needs for these types of intelligence affects the intelligence service's organization and operating procedures. Managers of this intricate process, whether in government or business, need to decide whether to make one intelligence unit responsible for all the component parts of the process or to create several specialized organizations for particular sub-processes. This question is explored briefly below, and more fully in Part VII.

Functional Organization of Intelligence

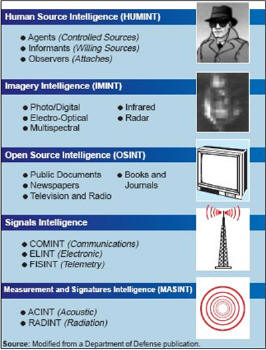

The national Intelligence Community comprises Executive Branch agencies that produce classified and unclassified studies on selected foreign developments as a prelude to decisions and actions by the president, military leaders, and other senior authorities. Some of this intelligence is developed from special sources to which few individuals have access except on a strictly controlled "need-to-know" basis.24 The four categories of special intelligence are Human Resources (HUMINT), Signals (SIGINT), Imagery (IMINT) and Measurement and Signatures (MASINT). The four corresponding national authorities for these categories are the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the National Security Agency (NSA), the National Imagery and Mapping Agency (NIMA) and the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA). DIA shares authority for HUMINT, being responsible for Department of Defense HUMINT management. Along with these four agencies, other members of the Intelligence Community use and produce intelligence by integrating all available and relevant collected information into reports tailored to the needs of individual customers.

Private sector organizations use open-source information to produce intelligence in a fashion similar to national authorities. By mimicking the government process of translating customer needs into production requirements, and particularly by performing rigorous analysis on gathered information, private organizations can produce assessments that aid their leaders in planning and carrying out decisions to increase their competitiveness in the global economy. This primer will point out why private entities may desire to transfer into their domain some well-honed proficiencies developed in the national Intelligence Community. At the same time, the Intelligence Community self-examination conducted in these pages may allow government managers to reflect on any unique capabilities worthy of further development and protection.

|

The next part of this series will appear in the October 11th Directions on Data newsletter.

Glossary

| ASD/C4ISR | Assistant Secretary of Defense for Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance |

| BI | Business Intelligence |

| CIA | Central Intelligence Agency |

| CISS | Center for Information Systems Security |

| CSRC | Computer Security Resource Center |

| DCI | Director of Central Intelligence |

| DIA | Defense Intelligence Agency |

| DII | Defense Information Infrastructure |

| DISA | Defense Information Systems Agency |

| DoD | Department of Defense |

| DODSI | Department of Defense Security Institute |

| FISINT | Foreign Instrumentation and Signature Intelligence |

| GPO | U.S. Government Printing Office |

| HUMINT | Human Intelligence |

| IC | Intelligence Community |

| IITF | Information Infrastructure Task Force |

| IMINT | Imagery Intelligence |

| INFOSEC | Information Systems Security |

| INFOWAR | Information Warfare |

| IOSS | Interagency OPSEC Support Staff |

| IPMO | INFOSEC Program Management Office |

| ISSR-JTO | Information Systems Security Research Joint Technology Office |

| JIVA | Joint Intelligence Virtual Architecture |

| JMIC | Joint Military Intelligence College |

| MASINT | Measurement and Signature Intelligence |

| MBTI | Myers-Briggs Type Indicator |

| MRI |

Management Research Institute |

| NACIC | National Counterintelligence Center |

| NCSC | National Computer Security Center |

| NIC |

National Intelligence Council |

| NII | National Information Infrastructure |

| NIMA | National Imagery and Mapping Agency |

| NIST | National Institute for Standards and Technology |

| NSA | National Security Agency |

| NSTISSC | National Security Telecommunications and Information Systems Security Committee |

| NTIA | National Telecommunications and Information Administration |

| OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

| OPSEC | Operations Security |

| OSD | Office of the Secretary of Defense |

| OTP | Office of Technology Policy |

| SCIP | Society of Competitive Intelligence Professionals |

| SIGINT | Signals Intelligence |

References

18 Captain William S. Brei, Getting Intelligence Right: The Power of Logical Procedure, Occasional Paper Number Two (Washington, DC: Joint Military Intelligence College, January 1996), 4.

19 Melissie C. Rumizen, Benchmarking Manager at the National Security Agency, interview by author, 4 January 1996.

20 Douglas H. Dearth, "National Intelligence: Profession and Process," in Strategic Intelligence: Theory and Application, eds. Douglas H. Dearth and R. Thomas Goodden, 2d ed. (Washington, DC: Joint Military Intelligence Training Center, 1995), 17.

21 Ronald D. Garst, "Components of Intelligence," in A Handbook of Intelligence Analysis, ed. Ronald D. Garst, 2d ed. (Washington, DC: Defense Intelligence College, January 1989), 1; Central Intelligence Agency, A Consumer's Guide to Intelligence (Washington, DC: Public Affairs Staff, July 1995), 5-7.

22 Garst, Components of Intelligence, 2,3.

23 CIA, Consumer's Guide, 5-7.

24 CIA, Consumer's Guide, vii.