That agonizingly slow conversion step is disappearing because of open interface and encoding standards developed collaboratively by users and vendors in a formal international consensus process in the Open Geospatial Consortium, Inc. (OGC). OGC's members have aligned their twelve year collaborative effort with other consensus standards efforts which have produced related standards for network-based distributed computing, particularly Web-based distributed computing, or "Web services." As a result, online geoprocessing systems functioning as "servers" can respond to Web-delivered commands from diverse "client" software processes to provide geoprocessing "services." These services can interactively retrieve, display or operate on a user-specified "bounding box" of data, which wasn't possible before. But standards-based services enable much more, such as:

- Real-time conversion of map symbols to suit the user's needs

- Robust access to sensor networks as spatial data

- New solutions to deal with semantic differences between data models

- Access to sophisticated GIS processing using only a Web browser

- Automated management of digital rights and security for geospatial data

- An open framework for location-based services

- Encoding of geospatial data in XML (eXtensible Markup Language), which opens many other possibilities.

The Federal Enterprise Architecture

Most of what happens in organizations involves processes and routines related to conveying and assimilating information. The Information Technology revolution has made it much easier to convey and assimilate information and this has had a profound effect on both public sector and private sector organizations.

In the US federal government, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is a body within the Executive Office of the President of the United States which is tasked with coordinating US federal agencies. The Federal Enterprise Architecture (FEA) is the product of an OMB initiative to comply with the Clinger-Cohen Act. It is a management tool that provides a common methodology for information technology acquisition in the U. S. federal government. A complementary and equally important goal is to ease sharing of information and computing resources across federal agencies, in order to reduce costs and improve citizen services. (For more information about the FEA and its Geospatial Profile, see "Federal Enterprise Architecture Gets a Geospatial Profile!" by Sam Bacharach, Directions, Sep 20, 2005.)

To quote from the E-gov page on the White House Web site:

In contrast to many failed “architecture” efforts in the past, the FEA is entirely business-driven. Its foundation is the Business Reference Model, which describes the government’s Lines of Business and its services. This business-based foundation provides a common framework for improvement in a variety of key areas such as:

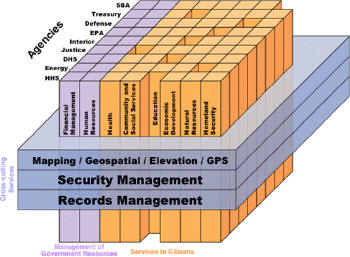

In a December 1, 2005 presentation (pdf) titled "Updates on the Latest Enterprise Architecture Guidance in Government," Dick Burk, Chief Architect and Director, Federal Enterprise Architecture Program, OMB included the following slide, titled "LoBs (Lines of Business) and Services":

- Budget Allocation

- Information Sharing

- Performance Measurement

- Budget / Performance Integration

- Cross-Agency Collaboration

- E-Government

- Component-Based Architectures

|

The next slide in Burk's presentation is titled "CONOPS," or Concept of Operations, which describes three activities: Architect, Invest, and Implement. Creating an architecture -- an orderly arrangement of parts -- is the first step that agency information system planners must take to implement the cross-cutting services shown in the figure above.

As the quote above from the White House E-gov page makes clear, the FEA is not intended to yield or describe a purely IT architecture, rather it is designed to assist in business process re-engineering that takes advantage of efficiencies enabled by IT solutions. The computer system itself -- or rather the vast network of federal computer systems -- is subordinate to the needs of the business. Component-based architectures (last bullet in the list above) are a means to that end. A standards-based component approach is what provides the efficiencies and the technical flexibility that lets business needs come first, before technology. Change is certain, and building on an open architecture keeps options open. The goal is to be able to gracefully modify business processes as they become outdated by technological change and other kinds of change, but not to make business processes slaves to earlier technology choices.

Geospatial Enterprise Architecture (GEA) Version 1.1

To ensure that the FEA would optimally meet the cross-cutting geospatial service needs of all the agencies, the Federal Geographic Data Committee and the Federal CIO Architecture and Infrastructure Committee (AIC) worked together with others in a group called the "FEA Geospatial Community of Practice" last year to create Version 1.1 of the Geospatial Profile for the FEA. That profile is also known as the Geospatial Enterprise Architecture (GEA). The GEA Version 1.1 is now in active use, providing guidance to agency architects and CIOs to help them identify and promote consistent geospatial patterns in their organizational designs. Detailed information about the process and the documents in work are available.

The EPA's Geospatial Information Officer, Brenda Smith, who is a member of the FEA Geospatial Community of Practice, has been presiding over activities in the OGC Technical Committee and Planning Committee designed to ensure good communication between the GEA process and the consortium membership. A number of other OGC experts have also been active in the Geospatial Community of Practice, providing insight into the adopted OpenGIS Specifications that comprise the OGC Web Services (OWS) suite of interoperability standards and also the proposed standards that are under development inside OGC.

Geospatial Enterprise Architecture (GEA) Version 2.0

Version 1.1 of the GEA was written for agency architects and CIOs. The FEA Geospatial Community of Practice is preparing Version 2.0 of the GEA for a different audience, the business managers in the agencies. The GEA Version 2.0 will be a management tool that provides a setting and structure for delineating interagency workflows and information flows - for mundane activities and crises - that involve geospatial information.

Since 9/11, it has become much more obvious that federal, state and local agencies depend on each other to fulfill their complementary missions in times of crisis as well as in ordinary times. Communication, including communication of geospatial information, can't work well during crises if it hasn't been practiced and proven in everyday situations. It should be noted that crises involve sudden encounters with new and unexpected requirements, so communication may not work anyway. Nevertheless, we need to be prepared and routine communication is a necessary prerequisite. No doubt with this end in mind, the US Department of Homeland Security recently became a Principal Member of the OGC.

Version 2.0 will explain why geospatial capabilities are so important and it will explain why they need to be seen as cross-cutting capabilities operating at all levels of the entire government enterprise, not at the level of particular agencies.

Loosely Coupled or Tightly Coupled Web Services?

According to Wikipedia, "Loose coupling is related to Web Services and Service Oriented Architecture. …. Loose coupling describes an approach where integration interfaces are developed with minimal assumptions between the sending/receiving parties, thus reducing the risk that a change in one application/module will force a change in another application/module."

Tightly coupled Web services are typically Web services that depend on proprietary interfaces, i.e., proprietary "assumptions between the sending/receiving parties." For example, if everyone in an agency uses a single vendor's software, a third party data provider might get permission from the vendor to provide a Web service for users to access that provider's data via the vendor's proprietary Web service interfaces. This might work very well for those who use that vendor's software, but it imposes a number of limitations:

- The agency assumes an additional commitment to buying software from a single vendor, during a time in the history of Information Technology when Web services are providing flexible, affordable and component-based online solutions that compete favorably with packaged desktop systems.

- There would be more competition and choice among data suppliers if the software supplier were "exposing" an open interface for accessing data supplier services.

- There would be more competition and choice among software vendors if the data supplier were "exposing" an open interface for access by software that accesses data services.

- Communication means “transmitting or exchanging through a common system of symbols, signs or behavior.” Deploying solutions based on a common system, i.e. standards, maximizes the kind of open communication that is the objective of the GEA. Practices that are artifacts of historical technical and commercial barriers between systems inhibit agencies from fulfilling their community information sharing responsibilities. Crises, and the future itself, will bring unexpected requirements for communication that will be met most readily if the agency has embraced open standards.

Conclusion

The FEA and the GEA represent a remarkable historical advance. Motivated initially by budget concerns, a wide-ranging initiative involving multiple linked policy decisions and consensus standards efforts has created a solid foundation that both leverages and supports the extraordinary and continually expanding capabilities of the Web and the Spatial Web. This is being done because it makes perfect sense from the standpoint of financial responsibility and good government.