While collecting business information and deriving insights about the commercial environment have been in practice since the dawn of commerce and competition, intelligence as a formal discipline began to take shape in 1980’s. Increasing competition, globalization and technology were beginning to dramatically alter traditional business practices, perspectives and stakes. Businesses sought ways to harness increasing amounts of data and information about customers, competitors and industry. Government intelligence models and practices were introduced and adapted to the commercial sector. Arising out of these developments, competitive intelligence (CI) is widely practiced today. Despite this, however, there is still some misunderstanding about what CI is, how it is practiced, and what it can achieve.

CI Defined

Much more than a catchphrase or a business trend, CI is the practice of examining the external competitive environment, including direct rivals, customers, suppliers, economic/regulatory issues and more - to support the development of more resilient, robust strategies and tactics. The outcome of intelligence should be meaningful, actionable, and, according to CI guru Ben Gilad, should provide "an insight about change and future developments and their implications to the company." The practice of CI follows established laws and ethics, and applies business and industry analysis rather than corporate espionage in generating intelligence and insights. The Society of Competitive Intelligence (SCIP) has a recognized code of ethics.

Some look upon CI as a luxury or a discretionary practice, but the value of CI is linked to business success - even survival. By definition, intelligence is intended to support decisions and actions. The insights generated from good intelligence enable decision-makers to minimize the risks and/or maximize the opportunities surrounding future actions. Intelligence can support even the most experienced and knowledgeable industry professional by providing additional insights about emerging or future developments.

It is important to note how competitive intelligence is distinct from related concepts and practices like business intelligence, market intelligence and competitive information gathering. While each of these terms have been used synonymously with CI and while there are overlapping tools, functions, and areas of research, each is specialized. Business intelligence (BI), as it is most often applied today, describes data mining and processing large amounts of business data and information to identify patterns and insights in a range of internal and external business functions. These functions may or may not be related to the examination of the external competitive environment or more directly competitive issues.

Market intelligence (MI) and competitive intelligence are complementary and can overlap in analyzing customers and markets. For example, CI and MI may each conduct or use positioning research to better understand how customers view products, services and brands compared to the competition. For the most part, however, the toolkits and applications for CI and MI are distinct. MI is concerned with understanding markets and customers in order to support decisions relating to market opportunities, new market development and market penetration strategies. To accomplish this, MI research and analysis tends to be based on market research techniques, including focus group research, segmentation research, price elasticity testing and demand estimation. CI, while considering customers and markets, tends to treat these as two of a number of forces that impact competitiveness and decision-making, and rarely focuses primarily on these factors. Industry rivals or broader pictures tend to take precedent.

Finally, competitive information gathering (or competitive research) is the component of CI that leads up to analysis, but lacks meaning and insights. Often, firms that simply conduct competitive information gathering mistake this practice for true CI. Organizations may gather news and other information about competitors or their industry - even generate informational products like alerts or newsletters. Without applying formal or informal analysis, as well as aligning the activity with a decision need, however, this practice stops short of intelligence.

So, having defined competitive intelligence, how is CI practiced?

The Intelligence Functions

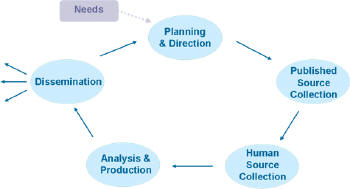

CI should be established according to the specific intelligence needs of the organization and its decision-makers. Good CI and useful insights rely on good intelligence questions, quality information, appropriate analytical tools and experienced practitioners. While there are other critical success factors that should be in place (adequate resources, management support, a culture receptive to honest discussion and insights, sufficient timeline and response time, etc.), CI practices tend to rely on the Intelligence Process (Intelligence Cycle), a framework rooted in a government intelligence model that was adapted and popularized in the commercial sector by CI guru Jan Herring.

|

- What is the timeline for locating a site, building the plant, establishing full manufacturing capabilities/capacity?

- What regulatory issues may they face?

- What is the cost of establishing the facility? Operating costs?

- Which products will be manufactured?

- Who will be the key suppliers?

The research function for intelligence involves two types of resources: published sources (also called secondary research or literature research) and human sources (also called primary research). Each is highly specialized in intelligence gathering and relies on skills specific to its function. In published source collection, a professional searcher or corporate information center trained in intelligence and business research gathers content from print or digital material. These materials range from competitor’s brochures to government filings to news articles to photographs. Human source collection derives information and expert insights from people knowledgeable about the topic or issue. This function is performed by skilled interviewers (often former journalists, industry specialists, and trained researchers), who may speak with former employees of a competitor, industry analysts, suppliers, customers, etc.

The analysis function is often essential to generating the intelligence and insights that are the aim of CI practice, particularly when there are multi-part KIQs, complex questions or a large volume of data/information involved. Intelligence analysis can involve more than 100 different models, spanning business functions, types of operation and industries. This function relies on intelligence information that may be collected using published sources, human sources or both. Taking into account the KITs/KIQs at hand, quantitative or qualitative models may be used.

Delivery is vital to the successful use of intelligence. Intelligence deliverables should be distributed to the right intelligence users, address their intelligence needs, be timely and be in usable form. These may range from scheduled reports and bulletins to products that address ad hoc intelligence issues. It is important to point out that news alerts may be vital information sources, but they are not substitutes for intelligence deliverables, which are tied to particular intelligence needs and often include analysis and recommendations.

The Intelligence Process should be considered a framework and a starting point for CI. Each function - and the process itself - requires customization to the specific needs and characteristics of an organization. Moreover, organizations may apply CI by developing selected functions internally and outsourcing other functions, as needed. For example, businesses often conduct routine published source collection on their own, but may outsource highly specialized research (e.g patent or trademark searches), formal interviews of human sources or complex analysis.

CI and LI

The relationship between CI and the emerging practices and tools that comprise location intelligence (LI) is rich and mutually beneficial. First, the significance of CI to LI can be found in the well defined and well established process, practices and applications of competitive intelligence. The term "location intelligence" is often used to describe the tools involved with mapping and business network analysis. This emphasis on tools (and data) over process and techniques may limit the capacity to fully generate intelligence. The generation of location intelligence may be more targeted, efficient and effective by modeling CI’s use of formal frameworks, its business discipline and its focus on decision-support. This will encourage a consistent application of location intelligence and help ensure that LI fulfills the intelligence needs of decision-makers.

Next, competitive intelligence may be used to gain insights on the location-based capabilities of a competitor, partner or supplier. In better understanding a company’s use of RFID in managing their distribution chain, for example, formally applying CI can tie this effort to the decision needs of the intelligence users, enhance the quality of the intelligence and help generate more usable results.

Finally, CI itself can more consistently apply location-based tools, technology, and applications to gather information, perform analysis and generate insights on competitors, markets and industry. Some CI practitioners have begun to adopt LI resources and techniques, like mapping and visualizing collected data, applying business geographics, gathering information from more widely available satellite maps and applying location-based analysis techniques (e.g. retail network analysis and Spatial Temporal Computing). Cost and complexity are sometimes barriers, but increased awareness and education about LI will encourage more practitioners to use these tools and enhance the generation of intelligence.

Reference

Benjamin Gilad, Business Blindspots: Replacing Myths, Beliefs, and Assumptions with Market Realities (Wiltshire, England: Infonortics, Ltd., 1996), p. xviii.

Resources

Knowledge inForm

(newsletter, glossary, e-books, online seminars, training)

SLA Competitive Intelligence Division

(bulletin, discussion list, SLA directory, online resources)

Society of Competitive Intelligence Professionals

(publications, training, events, industry news, directories)