Among the many mysteries that exist in the world, some of the most intriguing ones involve animals. In the big scheme of things, we know relatively little about the how and why of animals. We study them and have learned a substantial amount, but most of the time we don’t even know where they are. Will you turn a corner on the trail and come face-to-face with a mama bear and her cubs? Was that a shark fin that just came up between those waves? Will a deer pop onto the road in front of your car, and when and exactly where do we decide that it’s time to put a wildlife-crossing sign on the road?

Mapping modern settlement patterns is not particularly difficult. For people, we mark places on maps where houses or apartments already exist, and we circle it with a polygon and name it “Residential.” Or, it’s undeveloped space that we decide a priori would be a good place to live. We zone it Residential and enclose it with a polygon, and then one day, dwelling units may appear.

Mapping wild animal habitat is not so very different. We use evidence of nests, burrows, or dens. We keep track of where known food sources are, where the climate is known to be amenable, and where individuals of the species are known to have encountered humans. At some point, someone draws a polygon around it and calls it “Habitat.” Fortunately, we’re rapidly improving both the accuracy and precision of this process through the use of imagery from satellites, drones, and other techniques.

This means big data has come to the world of animal habitat too. The Global Biodiversity Information Facility disseminates data sets both large and small that include observations, specimens, and material samples. Data like these contribute to the Map of Life, an effort that spans animals as well as plants. Likewise, the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List also provides GIS-ready data for exploring the expert-estimated habitat of over 25,000 threatened species. That’s a lot of shapefiles.

Mapping animal movements – whether they are annual migrations, daily commutes, or exploratory wanderings – is a different type of challenge because different types of evidence are needed. We may know a cat was at Point A, and months later, at Point B, but we can only guess about the route in between. Expert trackers can read the signs of animal movement on the ground with keen insight, but the evidence can fade quickly. Under regular circumstances, animals leave none of the digital traces than humans do (where we get ATM cash, which toll booths we pass through, from where we make cell phone calls).

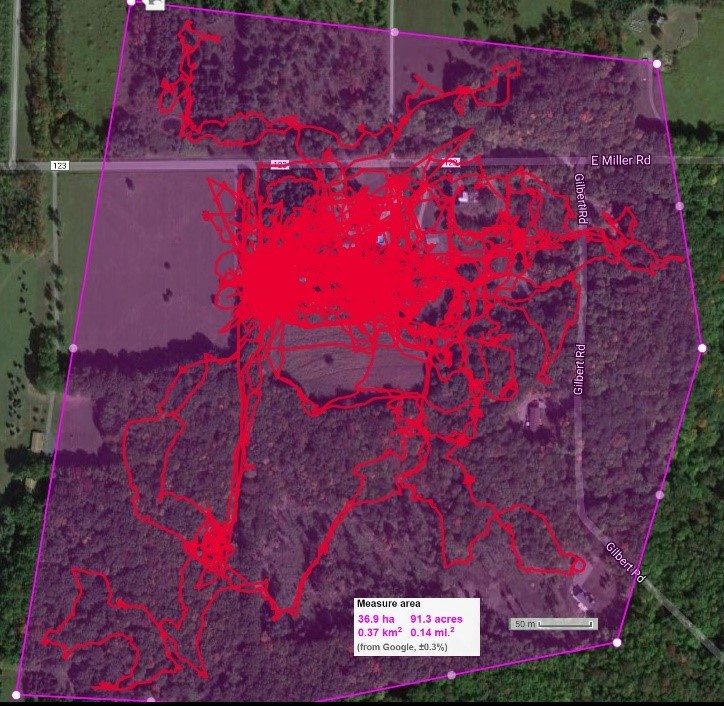

Where has Aloysius (Felis catus) gone to today? Photo shared with permission. (DM Photo/C. Witherup)

But sometimes, we find creative ways to add and interpret new and existing digital tracers. In a beautiful book published last year, Where the Animals Go: Tracking Wildlife with Technology in 50 Maps and Graphics, geographer James Cheshire and his colleague Oliver Uberti, shared dozens of stories about how wild animals are being watched and monitored for their safety and for scientific knowledge. GPS-enabled collars are often used for larger animals while ants must suffer the ignominy of having tiny barcodes attached to their bodies while they are observed. Recorded animal tracks illustrate how humans and the built environment impact natural habitats as well as routes of movement.

High-quality collections of wild animal movement data is precious information. Movebank has a Data Repository from which peer-reviewed, vetted data sets can be accessed. Track data for an individual animal might exist as a series of latitude and longitudes, for example. Software packages designed to aid in analysis and modeling of these types of tracking data are also shared and described.

More work may have been done globally in tracking bird migrations than for any other type of animal. Cornell University’s Lab of Ornithology supports eBird, an application that allows individual species sightings to be uploaded and shared. Abundance Models aggregate the data across the Western Hemisphere and enable the dynamic visualizations of seasonal migrations, like this one. Detailed track data increase the likelihood that we can mitigate human-animal conflicts.

Animal movement is least understood in the marine environment due to the inherent limiting factors of water and vast expanses. Most location-trackers do not function underwater, so those that rely on GPS may only record a signal during an animal’s infrequent, brief, and unpredictable surface intervals. We are left with not knowing really how to connect the dots, but it is fun to surmise and assume. Ocearch allows armchair marine voyeurs to imagine where Captain Wayne, a 250+ Mako shark that was tagged in March 2018, had been hanging out in the months since he last sent checked in, in July, to when he made an appearance this week with a surface “ping” of data. Whale mAPP is a collection of GIS-based web and mobile tools that allows the public to contribute to research on marine mammals. Citizen scientists have contributed thousands of sightings from across the globe, providing researchers with important information on distribution and habitat use. Project director Leilani Stelle uses the resulting GIS-based maps to analyze spatial relationships between mammals and human activities such as boat traffic. Less detailed, but more mesmerizing to watch, is the Smartmine Whale Tracker, where anonymous blue points drift among the currents.

Do animals have rights to wander discretely? Is their location privacy also controversial? Sometimes. Mass migration maps show aggregated data but the track of an individual animal puts it at risk from human predators as readily as it provides protection by its benefactors. What about our own pets? We have easy consumer access to the technology to keep track of our dogs and cats. You can set your own hypothesis and test it. Do you think Theo Cookie Paws stays nearby, while Lucy Long Legs explores distant neighborhoods? Cat trackers make great stocking stuffers!