Digital technologies have inspired and launched revolutions within the field of cartography in the recent past, bringing mobile mapmaking to our finger tips. Cartographers with an eye to the historic aesthetic are pursuing approaches to make new maps look old. But what about new ways to look at old maps? How are modern technologies being used to support research and investigations?

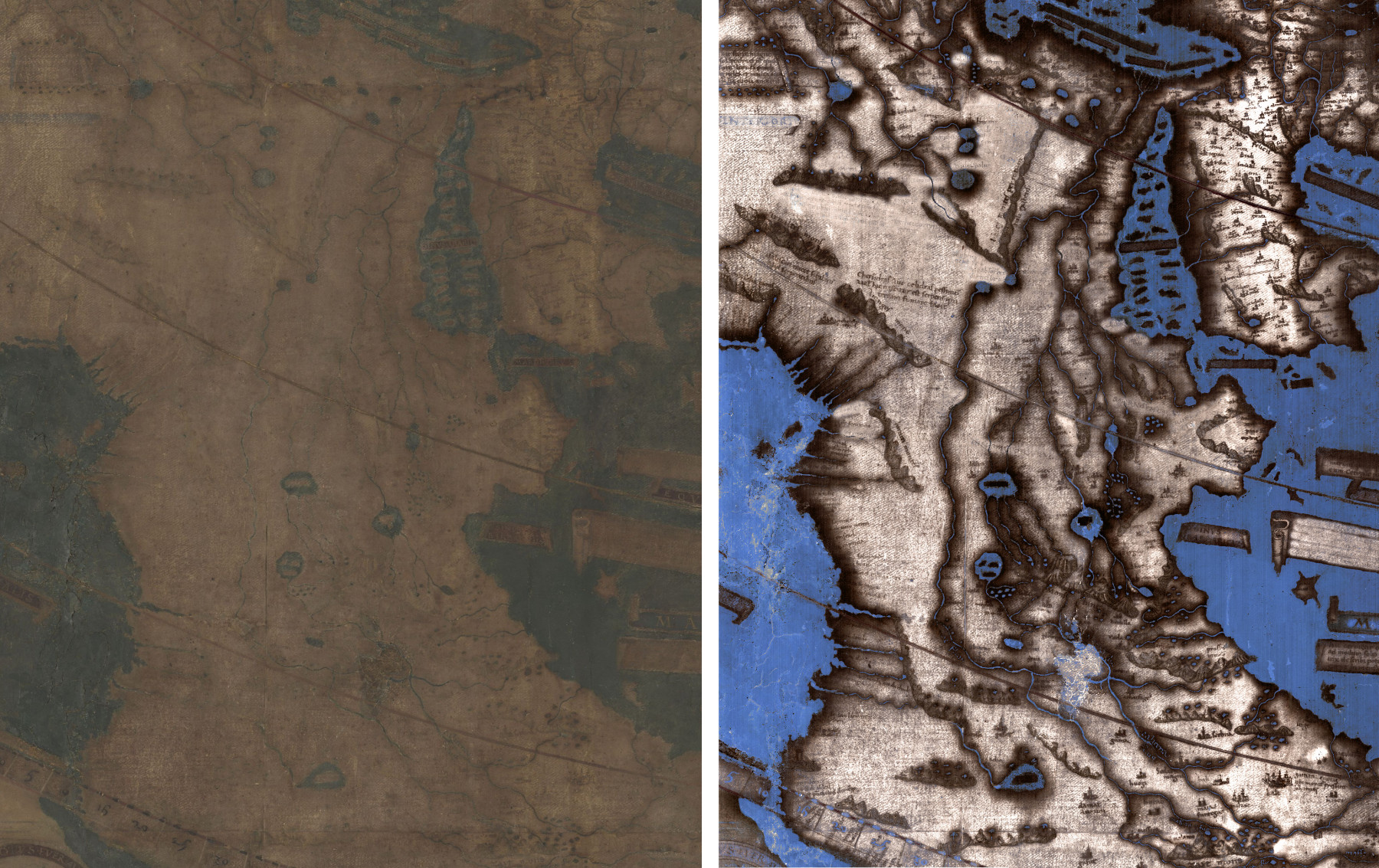

One way to appreciate historic cartographic treasures is to gift yourself new lenses with which to look. The Beinecke Library at Yale University has facilitated this process with the 1491 Martellus map in its collections. Produced by Henricus Martellus in the late 15th century during the epoch of global explorations, contemporary scholars have long wondered about the knowledge that the cartographer included in his production. Unfortunately, the map’s faded and deteriorated condition has greatly obscured almost all of its text, at least to the naked eye. What is there that we just can’t see anymore?

That’s the type of question that fuels The Lazarus Project, a research endeavor now based at the University of Rochester and directed by Gregory Heyworth. By using camera sensors that can capture light from wave lengths both smaller (ultraviolet) and larger (infrared) than the human eye can detect, Heyworth and his colleagues combine bands to produce new multispectral images of early manuscripts and other historical documents that allow us to see what had been otherwise obscured for centuries. Cartographic historian Chet Van Duzer oversees the Lazarus missions that deal with maps and globes, and he has worked closely with Roger Easton, an imaging scientist at the Rochester Institute of Technology, to produce the enhanced images of the Martellus Map, with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Remember that children’s story about Harry the Dirty Dog, who refused so stubbornly to take a bath that eventually his family fails to recognize him until after a good scrubbing? Viewing the before-and-after examples of these multispectral images signifies a similarly magical visual transformation.

An image of Africa on the Martellus Map as it appears in natural light (left) and an image of the same section that has undergone multispectral image processing (right). (Images by Lazarus Project/MegaVision/RIT/EMEL, courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.)

A particularly enticing feature of the Martellus map that was revealed was its descriptive texts. These proved challenging to uncover because Martellus had used different pigments for different texts, the same way we would choose a different color or fonts. Van Duzer recalls how Easton spent months tweaking the combinations of bands iteratively and uniquely to optimize the legibility one section of the map at a time. This labor of love was necessary to achieve the highest clarity and legibility possible, and Van Duzer has detailed his research findings in a new book, Henricus Martellus’s World Map at Yale (c. 1491).

Designing the multispectral camera system to be a mobile and transportable one means that historical objects that would otherwise never travel— such as a 500+ year-old map — can undergo data capture under safely controlled conditions in their home institutions. An even older map on which the Lazarus scholars, particularly Ph.D. candidate Helen Davies, have been working is a 13th century mappamundi in Vercelli, Italy. Previous attempts to clean and restore the map damaged it significantly, but the multispectral techniques are non-invasive and non-destructive. This is the only feasible way to approach such precious and unique items with the aim to generate clear views of the original content.

Gregory Heyworth working in Yale University’s Beinecke Library, with the Martellus map on an easel set in front of the camera. (Image courtesy of Chet Van Duzer.)

Text and images that have been compromised because of fading and material deterioration are one reason for lost research and educational opportunities. Other reasons include restricted access conditions for the protection of the items, or their physical characteristics; massively large maps are difficult or impossible to see in their entirety from one vantage point.

Digital versions address many of these concerns in a way that also enables greater access to the objects themselves. In the world of historical maps, the David Rumsey Collection at Stanford University is legendary. This vast collection of paper maps has been digitally scanned at such a high resolution that extreme viewing of the details is made possible at a greater level than is even possible to the naked eye (especially for those of us with eyesight compromised by age!).

Some of the maps in the Rumsey Collection are difficult to appreciate fully as scanned items, however, not because of their resolution, but because of their great size. For example, in the late 16th century, an Italian nobleman named Urbano Monte became fascinated with the idea of designing and producing a large-format world map in the round, one that would be about 10 feet in diameter when assembled. How was it printed in preparation for this? The individual “tiles” were 60 sheets within a manuscript atlas that could be unbound, cut-out, and edge-matched. His intent by design was that the 60 map sheets would be assembled into a flat circular map that would be backed with wood, then made rotatable about its central point, like a big wagon wheel. It is unknown how many of these Monte maps were actually produced, and it’s unlikely that any were ever assembled as envisioned.

Rumsey owns one of the Monte manuscripts, printed in 1587, and has provided the world with high-resolution versions of its individual sheets. Monte’s beautiful and captivating map has now been re-projected as a globe as one of seven world and celestial maps that are available in an augmented reality format through the AR Globe app (free; currently available only in iOS). Monte was imagining that a 10-foot diameter wooden disk that rotated would be a fascinating representation to explore the world, but he never had the chance to play with a mobile digital device! Being able to zoom and rotate his map – and the others that the app makes available is an exciting tool for exploration and discovery.

The 1587 Monte world map as a digital globe in virtual space (left) and a zoomed-in section of interest (right). Image source: Diana Sinton.

Not only are these maps aesthetically remarkable, but these digital formats enable unprecedented access for scholars. For example, Van Duzer has been exploring how Monte created his huge map — what sources he used for its geographical contents and images, and what inspired his map’s projection and rotatability. The number of historical maps may be a finite set, but there will increasingly be novel ways to consider these with new approaches and lenses.