In previous articles, we’ve explored how GST can address exponential scales, from subway stations to distant planets. Underlying these spatial scales are also temporal scales. An app like Nearby Explorer leads users to an airport terminal in moments, while images from New Horizons take over four hours to reach Earth from Pluto.

Now let’s get back to Earth, but not the Earth as we see it now. For millions of years humans have walked upon our verdant orb. I spent seven years as an archaeologist and had the opportunity to explore long-lost villages, hunting camps and burial sites. During that time, I also learned how elemental geography is.

Archaeology is a discipline of contrasts, both a social science and a physical science. It requires meticulous empirical data collection and speculative theory. On both ends of this spectrum, though, GST is an essential tool for discovering, preserving and recovering the past. In this article we’ll explore the history and potential for the use of GST in archaeology, along with some of the pitfalls.

From Lindbergh to LiDAR

As often happens in science, a new paradigm came by happenstance. Scouting potential air routes over Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula, Charles Lindbergh spotted Mayan ruins deep in the jungle. This led to his ongoing fascination with photographing the past from above. It was a fortuitous time, when motorized flight and portable cameras both became viable in the early 20th century.

Lindbergh’s subsequent adventures, in cooperation with the Smithsonian and other institutions, brought to light both the utility and feasibility of aerial archaeology. Now the past could be viewed from above, not just from the surface, and entire sites and landscapes could be taken in with a single view. New findings could be discovered in remote areas without the arduous fieldwork involved in hacking through jungle or traversing deserts.

Since the 1920s, mapping techniques have evolved at an astounding rate. Now we have satellites, photogrammetry, LiDAR, GPS and GIS. We can overlay massive amounts of data and build predictive models of where ancient sites are and where they might be found. However, this technology isn’t simply for the thrill of discovery. Pictures of the past paint a picture of our present, and the present and past could foretell our future.

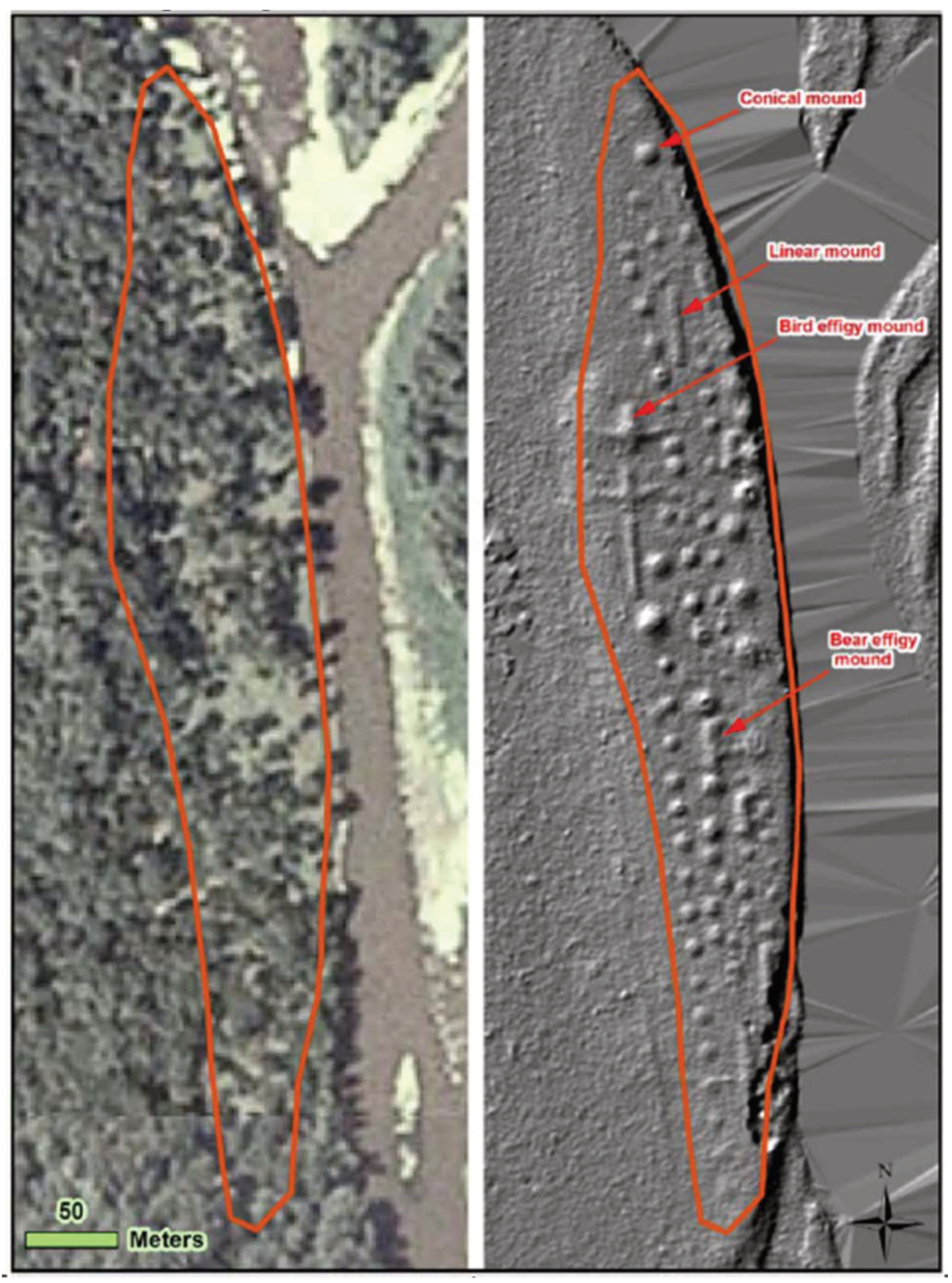

Image and NCPTT report: https://www.ncptt.nps.gov/blog/lidar-surveyor-a-tool-for-automated-archaeological-feature-extraction-from-light-detection-and-ranging-lidar-elevation-data-2012-07/

A Science of Contrasts

Archaeology is the study of the material past, the things people have left behind over millennia. When we think of it, or read about it, we picture a path of discovery. From the remains of soldiers in the U.S. Civil War to iconic sites like Machu Picchu, archaeologists have revealed long-lost pieces of human history.

But in the process of discovering the material past, it has to be compromised. Unlike other scientific fields, archaeology destroys what it discovers. Once an artifact is removed from the ground it can never be replaced exactly where it was. To explore the deeper past, more recent layers need to be taken away.

Fortunately, in recent decades this has changed. What GST and other modern technologies offer are methods to explore the material past without compromising it. As methodologies and technology have evolved, so has the potential to not only make new discoveries but to preserve what is left for future discovery and further research.

Looking Below from Above

Cartography has always been an essential element of discovering the past. To understand the tapestry of human presence on Earth we need to map it, both in space and in time. During my career in the early 1990s, GST was nascent in the field and the lab. I used a map, compass and cloth tape more than a transit, and a transit more than a GPS. Sometimes we had ortho photos, but these were used for navigation, not discovery.

Now we have incredible resources at our disposal. Since GST is scalable, we can map anything from a small site to an entire continent. Following are just a few examples of how GST is being used to reveal the rich history of humanity.

Not only can GST make new discoveries, it can map places where people can’t or shouldn’t go. The Plain of Jars in Laos is a vast, mysterious landscape of megalithic stones. It is also littered with the lethal remains of war, one of humanity’s oldest and ongoing undertakings. The conflict in southeast Asia during the 1960s-1970s left thousands of tons of unexploded ordinance. This obviously makes a very dangerous place to explore.

Using LiDAR-enabled drones, researchers have been able to map this area and begin to unravel its ancient mysteries without endangering field crews nor disturbing the site. The LiDAR and aerial imagery that was collected was used to create immersive 3D models to explore the site remotely and securely. Further missions will launch autonomous drones to explore the still-unexplored regions of the site, which lie under dense tree canopy.

One of the most iconic and richly-mapped sites in the world is Machu Picchu in Peru. In 1911 Hiram Bingham was the first American to map this site, using traditional survey methods. Since then many more mapping projects have been conducted there with more sophisticated techniques, from laser transits to LiDAR. As a team from MIT said in the MIT News, “We are just replacing tape measures and Mylar sheets with scanning tools and VR headsets.” However, Bingham wasn’t the first to map the mountaintop complex; Machu Picchu seems to have been planned and designed using what are essentially modern mapping and surveying techniques.

GSTs such as GPS, drones and LiDAR are functional at the site level, but the vast sweep of human history covers the globe. Along with space programs, NASA conducts Earth-based research across many disciplines, including archaeology, and is a pioneer in space-based archaeology. Global investigations and reconnaissance often lead to deeper local research. Starting with Landsat imagery, scientists reconstructed defensive systems in Turkmenistan along the Silk Road, a trade route that linked dozens of civilizations across thousands of miles.

Not All Destruction is Equal

While it is a destructive process, modern archaeology endeavors to do it scientifically. Unfortunately, there are many other threats to the material remains of human history. Often these are incidental or accidental, but in some cases, deliberate. Sites and artifacts can be affected by development projects, environmental factors or war.

In the case of Lava Beds National Monument, the destruction is a result of environmental factors. There, generations carved into the volcanic rock along the now-drained lakeshore. Due to centuries of aeolian erosion that continues to this day, these petroglyphs are fading away. The National Park Service and the University of Arkansas’ Center for Advanced Spatial Technology's program used ground-based LiDAR to build an enduring snapshot of these ancient carvings for future archaeologists to analyze.

GST cannot prevent all destruction, nor restore the past once it has been compromised, but is an essential tool in mitigating these losses. One of the richest areas of humankind’s past is now tragically one of the most dangerous places in the world. Across the Middle East, the stories of the past have become collateral damage.

In stable nations, LiDAR-enabled drones and field crews with sub-meter GPS can be safely deployed. In war zones such as Iraq and Afghanistan, even scientists risk death. The Kingdom of Jordan lies at the nexus of these scenarios — not at war, but caught in the crossfire.

A team from Australia has gone back to Lindbergh-era methods. As the ongoing wars continue to encroach on Jordan, archaeologists are conducting aerial reconnaissance flights to map known sites and find new ones. This program has built a deep archive of aerial imagery from this threatened region.

Archaeology for the Rest of Us

Few of us have the means and skills to actually go on an actual archaeological expedition. After seven years of fieldwork, my knees, back and wife said, “Enough.” The travel and manual labor were arduous to say the least, but it was worth it.

Fortunately, there are easier ways to explore the past. The National Park Service protects dozens of historic and prehistoric sites which are easily accessible, such as Canyon de Chelly in Arizona, originally mapped by Lindbergh. Organizations including the NPS, Crow Canyon and many others offer opportunities to volunteer on digs.

For those who would prefer a less daunting but still interactive experience, there are many opportunities. One if these is GlobalXplorer, “an online platform that uses the power of the crowd to analyze the incredible wealth of satellite images currently available to archaeologists,” according to its website. In the classroom, this is a fascinating method for teaching GST. One example is the American Museum of Natural History’s lesson, Traveling the Silk Road.

Destruction and Discovery

Just as archaeology is a combination of discovery and destruction, so is it also the discovery of destruction. The history of humankind is ultimately one of triumph and adaptation, but also one of conflict and tragedy: war, famine, drought and climate change. Elements of the past are destroyed while we discover new ones. There are countless discoveries yet to be made, each telling a unique story. Together, all of these stories create a panorama of our past...and our potential future. Hopefully learning from the mistakes of the past will lead us to a brighter future.